This marks something of a revival of my old GameSetWatch column, @Play. That one slowed to a halt because it was getting harder to avoid repeating myself, or had to resort almost to filler columns to keep it going. Particularly, I had a sense that I had said everything that needed saying. That's not a bad excuse to not say anything.

But then something happened. Like a gas spore struck by an arrow, roguelikes exploded.

Before, the closest to mainstream roguelikes were things like the Mystery Dungeon series, which were a stretch even in their native Japan, or the Diablo games. Now, it seems almost like every other new indie game on the Steam store is tagged roguelike, 108 of them as of this writing. Before our hiatus, Spelunky (one of the best real-time roguelike-inspired games) was a promising freeware creation. Now it's available for Xbox 360, PS3, Vita, and Steam, has fascinated hundreds of thousands of players with its terrific procedurally-generated gameplay, and has been the focus of many livestreams and YouTube recordings by star players like BaerTaffy and Bananasaurus. That indicates, to me, that the lessons of roguelike games have gotten out to some extent, and even been embraced, and I find that heartening. And ToME, under the name Tles of Maj'Eyal, is there, and ADOM is coming, and Desktop Dungeons has been there for a while! But it's not enough.

Anyway, there is no reason to restate the things I already said well enough on GameSetWatch. That site is still up (thanks Simon!) and all my columns, for their faults, are still there, and most of the things I said then are just as valid now. But it might be good to recap the basic points I made during its run. Here are most of them, in summary, and after that we can move on to new material.

All About @, Again

Possibly of use: The first column of the original run, from eight years ago, which contains a different, shorter, introduction.

|

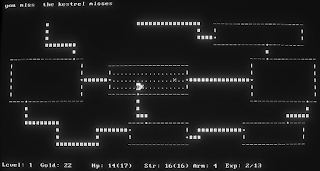

| rogue (from package bsd-nonfree) |

There is no official definition for "roguelike," nor an official body of any kind who could define it. It was adapted by fans to refer to games that took Rogue (1980) as a starting point and elaborated upon it. It itself took inspiration from the Dungeons & Dragons books (OD&D: 1974, AD&D 1E: 1977) and possibly earlier computer RPGs like dnd and Oubliette, which can still be played on the PLATO system running on Cyber1. Some of the earliest roguelikes, after Rogue, are nearly forgotten games like Advanced Rogue, SuperRogue, Ultra-Rogue, and Xrogue. It is very hard to play them in their original forms, but modern ports of some can be gotten from the Roguelike Restoration Project. Other prominent early roguelikes include Moria, Larn and Hack. Some of those games got their own variants: Moria was modified into UMoria and then Angband, Larn to ULarn, and Hack to NetHack. New variants are produced to this day. Angband has dozens of variants, and NetHack has gained quite a few just in the past few years. There's also standalone roguelikes ADOM and Brogue, among others. All of these are console-based, text games, but it is not necessary to be a console game to be roguelike, especially not now.

Rogue is one of the most interesting games, relative to what was floating around at the time of its creation, that there ever has been, and it's still pretty fascinating now. It was released the same year as Pac-Man. I refer to it in the present tense because people still play Rogue. It is a randomly-generated exploration game, using a simplified version of the original Dungeons & Dragons rules, in which the player guides a surrogate character through a treacherous labyrinth of monsters and traps. Rogue is particularly known for its great difficulty, its system of permanent character death (usually shortened to "permadeath"), its variety of play experience, its random game world, its tactical combat, the deep nature of its simulated world, its unique item identification system , and its replayability. Many of these things individually have given a game reason to be called, at one time or other, by some person, "roguelike." Because there is no official definition of the term, despite some creditable efforts like the Berlin Interpretation, lots of people use it to describe lots of different things, so let's briefly address each of the things in that list.

Difficulty: Rogue is very hard, and some later games are even harder. Some versions of Rogue are particularly hard.

| |

| moria (Linux Mint) |

But difficulty isn't enough by itself. There are lots of hard games that aren't really roguelike in nature, indeed most games released to arcades. Difficulty is by no means exclusive to roguelikes, but in subtle ways improves many of other other aspects here: if the game isn't hard, then why do you care about exploring unknown dungeons or identifying items?

Winning at Rogue is something to aspire to, with practice, experience, and (sometimes) lots of spoilers. But even with spoilers, winning is far from guaranteed, and for this fact looking up FAQs is considered to be fairer game than other, more static genres. This is because of--

Randomness: Every time you play Rogue, the game generates the dungeon anew.

But there are lots of games that use randomness but aren't roguelike. Particularly there are games that use it in a trivial way, that is, in a way that doesn't really affect the play. If you randomly generate a dungeon layout it may seem rogue-ish, but there are lots of ways you can lay out rooms and corridors that don't ultimately make any difference to the choices you make, not if you always stock that dungeon level with the same items and monsters, not if the critical path is always functionally the same, not if there isn't some resource management aspect to exploration that gives weight to that randomness. And it's also possible for a game to be too random, where the spikes up and down on the player power graph matter more than the player's skill. Usually good roguelike design is "spikier" than you might expect from playing other games, but still, if you're constantly running into top-of-the-line Dragons on level one, it's possible that the game is more about hoping the random dungeon generator doesn't generate impossible situations. That's especially important because of--

|

| NetHack 3.4.3 (console, Linux Mint) |

This is still the most controversial aspect of roguelikes, although it really shouldn't be. Games were like this from the very early days. You can't save your place in Space Invaders and return to it. Likewise, if your character dies in a Dungeons & Dragons adventure, at least at low levels, he's gone, your DM isn't going to resurrect him on a whim. At least, not if he's any good.

The common defense of permadeath given by enthusiasts, which I've been known to use myself sometimes, is that it gives weight to your decisions. But I think that's kind of a cop out. This isn't a special attribute of roguelikes, that's just what games are, it speaks more to a deficiency in modern gaming that gives players unlimited do-overs. It was a niche idea to be able to return indefinitely to saved positions, originally used for adventure games where exploring the consequences of decisions is part of the fun, that snuck out of its genre into other genres where, divorced of its context, it lost its original purpose and became something games just had to have, like happened later with experience levels, character unlocks and loot grind.

One variation on this idea I've heard bandied about lately has been called perma-consequence, the idea of there being other states than death that might not be simply reversible. Rest assured, we'll be returning to this idea.

Variety of play: This is not a commonly recognized attribute, but it gives a game a kind of roguelike feel. Random dungeon maps by themselves are not enough to make a game substantively different between plays. The player must be offered meaningfully different choices between games. In Rogue, depending on what items you find, or which enemies end up being most common, you may end up playing in an entirely different manner. For success, the player must to some extent adapt to the situation, rather than adapt the situation to his playing style.

This is such an essential part of the best roguelikes, yet it's recognized so little, that I'll probably be devoting a column to this one before long.

Tactical combat: The classic roguelike paradigm involves exploring a grid-based world where enemies have largely the same abilities as the player. Movement and attacks each take up an amount of time, and so one must frequently make decisions as to the best way to fight, or whether to retreat.

I'm not devoting that many words to this one because the meaning of roguelike has been drifting as of late. I'm still something of a die-hard, the word to me still tends to mean Turn-based Overhead Tactical Combat (Am I allowed to coin spurious acronyms, like "4X"? If so, how about TOTC, pronounced tot-ic?). The term roguelikelike has been suggested, but it puts me to mind of a certain shield-eating Zelda enemy. I suppose you could also quasi-roguelike (because "quasi" is a cool prefix) or rogue-ish. Just so you know, we'll be covering partly roguelike games too.

Depth of world: Rogue's game universe supports many different kinds of action, some of them useful only in obscure circumstances, but everything is useful at some point or other. Walls and floors can be searched for traps; you can rest in one place to regain hit points faster; rings provide special powers but at a cost of food consumption; you can throw arrows sure, but if you take a turn to wield a bow first they'll be much more effective; armor greatly increases your survival odds against powerful monsters, but wearing it makes you uniquely vulnerable to the one monster who cannot inflict physical damage on you; and the mere act of dropping a certain kind of item can save your life. Many actions turn up unexpectedly useful, but only experience (or spoilers) can tell you how.

If you consider depth of world to be measured in the variety of things the player can do, then this could also be considered one of the hardest hurdles to clear in learning how to play Rogue. The keyboard interface could be considered obtuse to present-day players. Its key layout is heavily inspired by the Unix text editor vi, using hjkl for orthogonal movement and allowing players to prefix some commands with numbers in order to repeat them (like 20s to search twenty times in place).

|

| Angband 3.3.2 (ASCII window, Linux Mint) |

Anyway, even if you know vi, there's plenty of new key commands to learn. In most cases these commands are pretty obvious by their letter, or are not too dangerous if you press keys to figure out. To eat something you press 'e', for instance, and to read something press 'r'. A few are more idiosyncratic: to drink a potion, you press 'q', for "quaff." 'w' stands for wield and is how you equip weapons; Shift-'W', however, means wear, and is how you put on armor. One thing that's nearly universal to all roguelikes, however, is 'i', for inventory.

Item ID: This is one of Rogue's less-copied features, but one that has a profound effect on its gameplay. As other games hosting random dungeons have increased in number, this has become probably Rogue's most defining characteristic, and the one enamored-of most by the Hack-like branch of its descendents.

Scattered throughout the dungeon are randomized magic items going by different descriptions, like "orange potion" or "lapis lazuli ring." Their purposes are scrambled within their item classes from a number of possible effects that are consistent for their descriptions. An orange potion, for instance, may be extra healing one game, gain level the next, and blindness in still another. Importantly however, while their functions change from game to game, within a single game they're the same: orange potions won't suddenly take on a different quality but remain consistent in function until you die. (This is one reason that permadeath is important to Rogue.)

Mixed in with the good magic items are some bad ones – drinking a potion of blindness is generally a pretty bad thing to do in Rogue, but because you don't know which kind of potion will blind you before drinking, you usually get burned by each type once, at some point. This can be escaped, however, through the use of a special kind of item, the scroll of identify, which will infallibly identify one item you're carrying. Unfortunately, scrolls are themselves one of the random item types, and so you will have to use-test at least a few items before you find out what they are. (I call use testing items to find out what they are "trial ID," as in trial-and-error. I'm not sure why I started calling it that; maybe it reminds me of drug trials.)

Once the game is satisfied that you definitely know what an item is, it will rename it for convenience: it'll stop calling the orange potions and instead say something like "potion of extra healing." Many roguelikes that adopt an item identification system, especially the more difficult variants of the Japanese Mystery Dungeon games, will identify these items immediately on their first use, under the philosophy that if you took the risk in using it you deserve to know what it is, but Rogue does not always do that. Instead, if you use an item, it will be identified for you if the game judges its effect was obvious enough. Sometimes this is nearly always (it's usually pretty obvious when you've been blinded), but other times may be situational. A few kinds of items will never be identified from use, but clues may be provided upon use. Sometimes the game will ask "What do you want to call it?" after using something, asking you for a name. It will then rename the item to that, saying, depending on what you entered, "a potion called extra healing." You can also manually name items with a special command.

By the way, Rogue's item identification system most likely has its root in 1st edition Dungeons & Dragons, which has a number of cursed and otherwise-bad magic items that exist mostly to be confused with good items of the same type. In AD&D however, many of these items were outright lethal, like the Bowl of Watery Death, which existed only to screw over players who thought they were getting a Bowl of Commanding Water Elementals. Rogue versions, at least, are much fairer: no Rogue magic item can kill you by itself, although some may end up deadly combined with other situations.

|

| Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup 13.1 (console, Linux Mint) |

A game where you can't die, but is varied enough that each game feels like its own adventure, is, in one sense, more roguelike than a boring game with permadeath, random dungeons and scrambled magic items.

Here are some other relevant points I've argued for over the years:

- While trends and fads may make some things seem more interesting to us, at different times, than others, game design doesn't go obsolete.

- Grind is bad; players should not be kept from the "good stuff" in a game by having to pay their dues in terms of time played. This is degenerate game design. Think carefully about the consequences of this; while there are fewer always-bad things a designer can do than you might think, as a designer, you know why you're doing it.

- To avoid becoming grind, player improvement must come with risk of loss, either of resources or outright game failure.

- While permadeath can be good, preserving state in a game long-term, between games, is a very interesting idea – it's what gives a game continuity of experience, that makes a play one long game instead of string of isolated, unrelated situations. There is probably an upcoming column on this matter.

- Randomness can be very interesting in a game, if used properly. However, random dungeons by themselves are not enough, if the contents of those dungeons is always the same. You might as well just have pre-made dungeons in that case.

- Pure randomness can be worse than pre-written content; at least the latter is presumably playable once.

- Good random content generation filters its randomness, uses it to create good content while remaining both challenging and winnable.

- That said, good roguelike design doesn't take it easy on the player based on his state. If you're low on health, sources of healing do not magically become more common. This is because roguelikes are fundamentally exploration simulations, and cooking the dice in favor of the player is breaking the simulation. Roguelikes are not play experiences, they are challenges; you don't play them to feel empowered, but to see what will happen.

- Longer games must be more fair to the player, must be more certainly winnable, and must generally be easier. For all these reasons, shorter roguelikes tend to be best. The sting of a loss is proportional to the amount of time spent playing.

- Balancing this out, winning a good roguelike game does not make future wins foregone conclusions. A well-designed game can still be challenging and fun even after many victories.

- The first time you finish a good roguelike, you generally have the feeling that you lucked out. You probably did, but you learned a lot to get there.

- Tactical combat is considered by some to be an essential element of roguelikes, but increasingly many interesting examples of the genre do not require it.

- Some roguelikes have interesting features by which the events of successive games can modify the game world, and affect later games. At best this results in features like NetHack's bones levels and Shiren the Wanderer's multi-game quests; at worst, the player may end up having to "level up"* the game world to make it easier in order to have even a chance at winning. We'll talk about this more when we get to reviewing Rogue Legacy.

This is nothing that long-time readers should look askance at. If you are such a reader, welcome back! If you're a newcomer, don't worry! All new readers receive a pile of food and some darts completely for free, and one complementary expensive camera. Be sure to take lots of pictures of the wildlife; your life may depend upon it. When (if?) you see Twoflower tell him I said "Hi." Until next time, once again, this is John "@rodneylives" Harris, still waiting by those down stairs, wondering what happened to that dog.

* A final note. This is going to sound pedantic but I don't care, I spent years writing @Play and figure I've earned some orneriness. I insist that the proper term to use in roleplaying games, if you have to use experience levels at all, is to "gain a level," not to "level up," which is Engrish come home by way of console JRPGs. I am playful with this insistence because I don't actually care. But if I were ever to edit a New Yorker-style magazine somehow devoted to video and computer games, then this would be the first thing I threw into my gnomish and inscrutable style guide. And diaereses over adjacent vowels in separate syllables, of course: this is a civilized column.

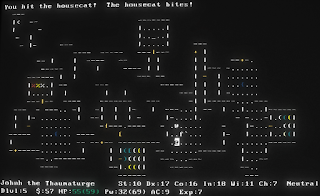

All screenshots taken in cool-retro-term, running on current Linux Mint. It's the best way to pretend you're back in the 80s playing on a flickering CRT!

--------------------

@Notes:

As said above, the 7DRL Challenge is going on right now, where a bunch of guys try to create a roguelike game in a week. A few important roguelikes, like DoomRL, got their start as 7DRL jamgames, and it's notable because every year there are both an unusually high number of both entries and awesome projects. You should check it out! One Twitter user who's been following them is @dungeonbard. Maybe worth checking out?